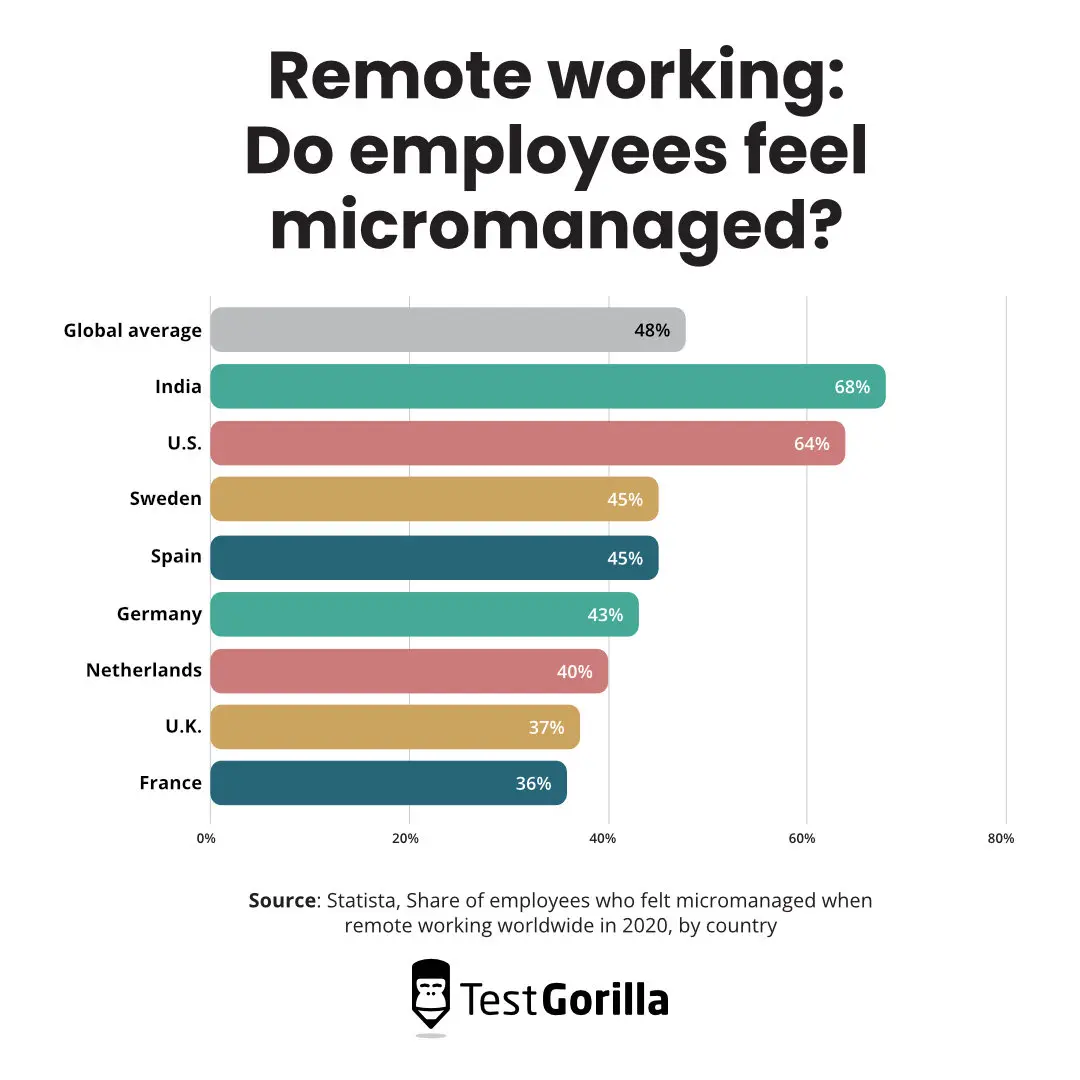

Micromanagement continues to be one of the biggest issues most workers will face in their careers despite the devastating consequences this management practice can have. A recent Monster poll about workplace red flags found that the biggest red flag for 73% of workers surveyed was micromanagement and that 46% of workers would leave their job because of it. Even in the post pandemic world where more workers are finding opportunities to work remotely, 16 % of U.S. based companies are now fully remote, this stubborn management trend continues to persist. In fact, according to Harvard Business Review, 60% of companies with remote workers use employee monitoring software, and these companies are starting to act on what that software finds. All of this is leading to workplace cultures that lack trust and team members who have decreased morale and engagement.

This article aims to explore what micromanagement is and why it is so harmful. We will also look at when normal management becomes micromanagement, and what best practices leaders can leverage to avoid this harmful practice.

What is Micromanagement?

Gartner defines this management style as,

“a pattern of manager behavior marked by excessive supervision and control of employees’ work and processes, as well as a limited delegation of tasks or decisions to staff.”

Micromanaging tends to be about tasks, the need for control, and is highly tactical. This management pattern can be harmful. When micromanagers focus just on the immediate tasks, they neglect the bigger picture and hinder long term progress. Micromanagers that cling to control end up undermining their team’s sense of independence and potential. In addition, when a micromanager dictates every step of a process, they can create an environment that suffocates creativity and professional growth.

It is not a surprise that team members that are micromanaged tend to surrender their initiative and creativity. Micromanaging replaces the team member’s ingenuity and performance with the manager’s ingenuity and performance. Here at ACV, we hire our software developers for their initiative, ingenuity, and creativity. Micromanaging in our culture would undermine the very reason we hired our software developers.

Micromanagement: The Pitfalls

There are organizational symptoms that appear when a manager is micromanaging. Here is a quick run down to allow you to assess if your organization might be micromanaged or if you are a micromanager.

1. Over-involvement: Micromanagement occurs when a manager becomes excessively involved in every detail of the work. This can lead to stifling creativity and autonomy among team members, which may affect their motivation and productivity. It can also lead to a busy calendar for a manager who feels they need to be in every meeting their team is in.

2. Lack of Trust: When a manager micromanages, it can signal a lack of trust in the team’s abilities. This undermines their confidence and can result in disengagement or resentment. If a manager finds that the team struggles to have healthy conflict, collaborate, or resist sharing information, it could be a sign that the team has underlying trust issues.

3. Inefficiency: Constantly checking on progress, making frequent changes, or demanding minute adjustments can slow down the workflow and lead to inefficiencies. It is often more effective to set clear guidelines and then step back to let the team do their work. If a manager finds that the team is struggling to deliver work, control scope, or are frustrated by too many changes, there may be an opportunity to increase the team’s efficiency.

4. Decreased Morale: Being micromanaged can be demoralizing. It can lead to increased stress and dissatisfaction among team members, which can ultimately impact the quality of the work produced. Team members may struggle to define the value they provide to the organization leading to dissatisfaction with their job and anxiety over job security

Is Micromanagement Always Bad?

Management is rarely black and white, and this remains true with micromanagement. There are specific situations in which a manager may have no other choice. For example, when the team’s skills don’t match their assignments, a manager may have to decide things for them and take on some of their work. Micromanaging sometimes is a manager’s last resort for getting things done.

Even in this example however, this should only ever be done in the short run. The manager should really be setting an example to help the team learn and grow. Once the example has been established, the manager should back off and allow the team to follow the example. A manager in this situation should also consider providing more training or making staffing changes, to help the team better align with the work as this will be more sustainable.

Management vs. Micromanagement

From my experience managing managers, I recognize that many managers don’t intend to be micromanagers. Managers who transition from a direct contributor roles sometimes struggle to make the transition to management. They get excessively involved in the details because in their previous role they had to. For those struggling, I find it helpful to distinguish what is the difference between management and micromanagement.

Managing is about setting direction, providing clear expectations, and supporting with training and resources. U.S. Army general George S. Patton, famously said:

George S. Patton

George S. Patton

"Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do, and they will surprise you with their ingenuity."

The act of management is strategic in nature where micromanagement is tactical. Managers strive to control the expectations and the environment where a micromanager tries to control the team member.

Keep in mind that delegating, providing expectations, and holding people accountable for their performance is not micromanaging. In fact, when managers don’t do these things, it can lead to team members who are under managed.

Finding the Balance

There is no one correct style when it comes to managing teams, and therefore, there isn’t a single management style that can be adopted that will allow the adopter to completely avoid micromanagement pitfalls. There are best practices however that may allow managers to be hands-on, without necessarily micromanaging.

1. Set Expectations: A manager should set clear guidelines and objectives for each project. When the team is aligned and understands what they need to do, there is less need for constant oversight. At ACV, we use project kickoff meetings for exactly this reason. At a project kickoff we can establish what needs to be done, who is going to do it, and when we think we will be finished.

2. Trust Your Team: Once clear guidelines have been established, and tasks have been delegated, the team needs autonomy to execute. Managers should trust their teammates’ expertise and allow them to make decisions. This will foster a positive and productive work environment.

3. Time Your Help: Time your help so it comes when people are ready for it. The best thing a manager can do sometimes is just listen. Initiative-taking individuals will want to tackle challenges themselves and a manager that steps in too soon may encroach on these desires. It is best to often let a team take on a challenge first, even if that means they may struggle. Once the team has a better grasp of the challenge they are facing, and if they continue to struggle to overcome it, they may become more receptive to help from the manager.

4. Offer Support, Not Control: If you do step in to help a team, explicitly clarify that you are stepping in only to help. It is important to remember that managers wear multiple hats, including evaluating performance. When they step in, even with the best intentions, teammates may interpret their actions as a sign that they are not doing an adequate job. It is important that managers specify they are only there to help, not to judge, take over, or replace anyone on the team. Once the team is on their way again, the manager needs to be able to back off and go back to just listening.

5. Align: A highly motivated manager may want to jump in and help a team at every opportunity, but remember that management is not about the manager, but about the teammate. A manager should align their involvement, both the intensity and the frequency, with the team’s specific needs. A team of experienced teammates may not need the same level of involvement from the manager as a team of inexperienced teammates. A manager should have a good sense of their teammates’ strengths and weaknesses and should align their involvement based on that data.

Practice and Reflect

Management is never easy, and it is a skill that requires constant practice. Good managers are constantly learning and reflecting on their own performance, and this is true when it comes to managers who want to avoid micromanaging. Remember to focus on the strategic aspects of managing, resist the tactical, and you will be in a better position to cultivate more innovative, effective teammates. You will also free yourself up to do the things that only you can do. In the end, you and your team will work more efficiently and effectively while enjoying a culture that engages and trusts teammates who are creative, initiative-taking, and independent.