William Rogers

William Rogers

William P. Rogers was an accomplished and principled man. He had served as the United States’ Secretary of State from 1969 to 1973 working with the Nixon Administration. He had received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his service but retired from his life of politics when asked to assist with the Watergate scandal. William Rogers’ time serving his country was not over, however, as a historic event in January 1986 would bring the government back into his life.

On January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger broke apart 73 seconds into its flight killing all seven crew members aboard. The President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, was set to deliver the State of the Union address that evening but postponed it instead to talk directly to the nation about the tragedy. In the days that followed, press interest in the disaster increased dramatically but NASA did not make key personnel available to answer questions. This led to wild speculation and conspiracy theories about what caused the Challenger tragedy. To address the rumors President Reagan created the Presidential Commission on the Challenger Accident and requested William Rogers chair it.

13 years after his retirement William Rogers would need to deal with the finger pointing politics of the US government, find the underlying cause of the Challenger disaster, and develop recommendations for how to prevent such a disaster from ever happening again. William Rogers needed a postmortem.

What is a Postmortem?

A postmortem is a process of analysis and reflection conducted after a project or event has concluded, particularly when it did not go as planned. The goal is to identify what did and did not work, why, and to use these learnings to improve.

The word postmortem first appeared in medical literature in 1734 and means “after death.” Autopsies are a postmortem activity for example. The process proved to be so effective at advancing the medical field, leaders started adopting it across multiple businesses and industries. In the modern age, postmortems are powerful tools for project management, tech companies, and government agencies to increase operational efficiency.

Why Have a Postmortem

A properly conducted postmortem is an excellent way to document lessons learned, identify the root cause of a problem, learn from mistakes, improve processes, enhance team communication, build a culture of accountability, facilitate better decision making, and build stakeholder confidence.

Document Lessons Learned

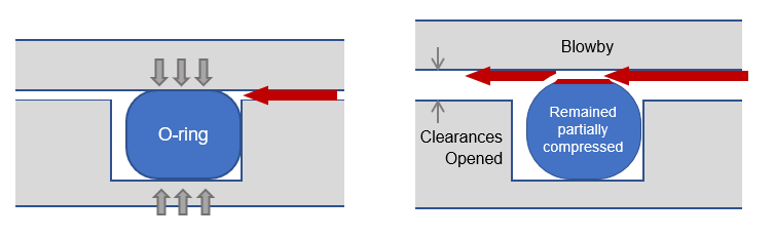

Postmortems create a record of insights and actions that can be referenced in the future, serving as a valuable resource for continuous improvement. On June 6th, 1986, approximately five months after the tragedy, the Rogers Commission produced the Rogers Report, more formally known as the, “Report to the President By the Presidential Commission On the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident”. This was a postmortem report that included nine recommendations on how to improve the shuttle program.

Identify Root Causes

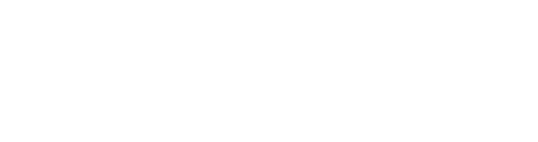

Postmortems help uncover the underlying reasons for failures or issues, allowing teams to understand what went wrong. In the case of the Challenger tragedy, William Rogers’s team discovered that the immediate cause of the disaster was the failure of the primary and secondary O-ring seals in a joint in the shuttle’s right solid rocket booster (SRB). The O-rings, when subjected to cold, lost some of their elasticity. This meant that after the O-ring was put under pressure and that pressure was then removed the O-ring didn’t expand to fill the gap created. This gap allowed hot gases to escape the SRB and lead to the disaster.

O-ring Defect

O-ring Defect

In addition, the commission found contributing causes of the accident. One such contributing cause was the failure of both NASA and its contractor, Morton Thiokol, to respond adequately to the design flaw. Another cause was in the decision-making process that led to the launch of the Challenger shuttle. The O-ring defect had been known by NASA for years, and even when the engineers recommended to not launch the shuttle due to the unusually cold weather, senior management overruled them.

Due to the override, the higher Flight Readiness Review (FRR) never heard the engineers’ concerns. In the postmortem the higher FRR admitted that they would have stopped the launch had they received the concern. The reason they did not have this information was in large part due to the management structure at NASA and the lack of major checks and balances.

Learn from Mistakes

Postmortems provide an opportunity to gain experience from past failures, reducing the likelihood of repeating the same mistakes in the future. In the case of the Challenger tragedy, the Rogers Commission produced nine recommendations on how to improve safety in the space shuttle program. Upon receiving the Rogers Commission Report, President Reagan assigned an action item to NASA telling them to report back within thirty days as to how it planned to implement the recommendations.

Improve Processes

Insights gained through postmortems can lead to improvements in workflows, practices, and systems, enhancing overall efficiency and effectiveness. The Rogers Commission recommended that NASA encourage the transition of qualified astronauts into agency management positions. These individuals would bring flight experience and a keen appreciation of operations and flight saftery. In terms of system enhancements, the postmortem report recommended that NASA make all efforts to provide a crew escape system for use during gliding flight.

Enhance Team Communication

Postmortems foster open dialogue among team members, encouraging transparency and collaboration. The Rogers Commission postmortem found that the Marshall Space Flight Center tended to insulate their management, and this tendency led to a miscommunication between the Marshall Center and other vital elements of the Shuttle program. The Commission recommended to tear down the management silo, and record both the Flight Readiness Review (FRR) and Mission Management Team meetings. In addition, the Commission recommend that NASA institute a policy of having the flight crew commanders attend the FRR, participate in acceptance of the vehicle for flight, and certify that the crew is properly prepared.

Build a Culture of Accountability

Postmortems help promote a culture where teams take responsibility for their actions and outcomes, leading to better performance. At NASA, the Rogers Commission recommended the Shuttle Safety Panel to help drive accountability in the areas of shuttle operation issues, launch commit criteria, flight rules, flight readiness, and risk management. In terms of holding NASA accountable, the report suggested the creation of the Independent Oversight Committee to specifically oversee the redesign of the Solid Rocket Motor.

Facilitate Better Decision Making

The insights gained during a postmortem can inform better decision-making in future projects and help teams to anticipate potential pitfalls. Recommendations like having more astronauts in management, criticality review and hazard analysis, and overhauling the shuttle management structure were all designed to help NASA make better decisions in the future. In each case, the recommendation focused on getting the right information in front of the right people and designing a system of checks and balances that would guarantee that it happened.

Builds Stakeholder Confidence

Demonstrating a commitment to learning from failures can build confidence among stakeholders, showing that the team is proactive in addressing challenges. Keep in mind that one of the reasons that the Rogers Commission was formed by President Reagan was because NASA had not made key personnel available to answer questions about the Challenger tragedy. The Rogers Commission’s postmortem process, and the subsequent 256-page report that they produced, highlighted just how seriously they took the accident and showed how actionable learnings could be gleaned from the disaster. In the end this calmed the press and the American people, and 32 months later, NASA resumed shuttle flights.

Rogers Report Signatures

Rogers Report Signatures

How ACV Does Postmortems

While our process is not as rigorous as the one used by the Rogers Commission, ACV has borrowed liberally from this example. ACV has weekly postmortem reviews that are blameless. The idea is that the postmortem is not about assigning blame but coming together to understand what happened and collaborate on ways to improve going forward. This also creates a culture of psychological safety and makes teammates more willing to raise problems and concerns knowing that there will be no backlash.

Just like the Rogers Commission, the goal of ACV’s postmortems is to identify main and contributing causes, and develop a series of recommendations that ultimately help build stakeholder confidence.

Here is how ACV structure’s their postmortems to accomplish this goal.

1. High Level Summary of What Happened

2. The Severity Level and the Impact

3. The Resolution

4. The Root Cause Analysis

5. Action Items

6. What Went Well

7. What Did Not Go Well

8. Appendix and Supporting Information

High Level Summary of What Happened

The high-level summary is a three to five sentences paragraph that help everyone come up to speed on the context of the problem.

This section should answer:

1. What triggered the problem?

2. How was the problem detected?

3. How was the problem resolved?

4. What was the impact of the problem?

Severity Level and Impact

ACV designed this section to deep dive into how much of an affect the problem had on the business. ACV measures this in terms of revenue loss, affect on the product or customer experience, and internal impacts such as delays and consumption of software developer time. This section should include digestible charts or metrics that show the analysis.

Resolution

This section should be a three to five sentence paragraph describing the main tasks taken to fix the problem. Each main task description should include the reasoning of why the troubleshooting team did this task and the impact it had. After reading this section, the readers should have a good understanding of why the resolution fixed the issue.

Root Cause Analysis

The purpose of this section is to dig into why the problem happened in the first place. This section should support and validate the resolution. The analyst can use it to highlight where additional action items are required to ensure that the problem does not happen again. At ACV, we use the 5 Why Analysis to help discover root causes.

For more information on how to perform a 5 Why Analysis, I highly encourage checking out Understanding Problems With the Five Whys Analysis.

What Went Well

It is easy during a postmortem review to only focus on the negative. This section is to highlight the positive and celebrate the wins that the team had while addressing the problem. Postmortem writers can use this section to call out behaviors from specific teammates that contributed significantly to the resolution. Writers can also use it to highlight how the process operated as intended, or how safeguards triggered appropriately. Use this section to celebrate the wins.

What Did Not Go Well

This section goes over areas that need improvement. This can be things like response time or breakdowns in communication. It could cover gaps in monitoring or alerting. It can even cover the postmortem process itself. Remember that feedback is a gift as it gives important information on how to make the process better.

Appendix and Supporting Information

This section is to capture any additional information that helps support the postmortem. Typically, this can be things like timelines, screenshots, graphs, or other supplemental material that helps the reader understand the problem, action items, or concepts that the postmortem discusses. The more information that the postmortem can provide the reader, the better off the reader will be at detecting and preventing the problem the next time.

Moving Forward with Confidence

In the end, the Rogers Commission was considered a success. NASA established the Office of Safety, Reliability, and Quality Assurance. Subsequent missions were launched with the redesigned solid rocket booster (SRB) and the Challenger shuttle was replaced with Endeavour. Endeavour would have its first mission in May 1992 and would go on to have 25 successful missions until its retirement in May 2011.

The Postmortem process worked extraordinarily well for NASA. Business that are struggling to develop a culture of accountability, stability, and performance should consider leveraging postmortems. They may be surprised at how effective this tactic can be.

Challenger Crew: (from left): S.Christa McAuliffe, Gregory B. Jarvis, Judith A. Resnik, Francis R. "Dick" Scobee, Ronald E. McNair, Michael J. Smith, and Ellison S. Onizuka

Challenger Crew: (from left): S.Christa McAuliffe, Gregory B. Jarvis, Judith A. Resnik, Francis R. "Dick" Scobee, Ronald E. McNair, Michael J. Smith, and Ellison S. Onizuka